First, Do No Harm. Second… Do Nothing?

Denial may be central to maintaining addictive behaviors. But why does denial extend to doctors treating — or, more accurately, not treating — patients? Are they in denial too?

Researchers Melinda Campopiano von Klimo, MD; Laura Nolan, BA; Michelle Corbin, MBA; et al conducted a search of medical literature published from January 1, 1960, through October 5, 2021, to better understand doctors’ approach to people experiencing addiction and displaying addictive behaviors.

The researchers reviewed 283 articles in medical publications PubMed, Embase, Scopus, medRxiv, and SSRN Medical Research Network. They sought publications that described physician-reported reasons for reluctance to address substance abuse and addiction. When the results were tallied one condition rose above the rest with regard to their reluctance to engage patients: institutional support.

“The most common reasons given by physicians to explain their reluctance were a lack of institutional support, knowledge, skill, and cognitive capacity,” summarized an interview with one of the researchers involved.

Lack of Institutional Support

How does the perception of a work environment impact physicians? According to the NIH:

“Institutional environment” refers to factors like lack of support from a physician’s institution or employer; insufficient resources, such as staff and training; challenges in organizational culture; and competing demands. This reason was cited in 81% of the studies reviewed, followed by insufficient skill (74%), lack of cognitive capacity to manage a certain level of care (74%), and inadequate knowledge (72%).

The researchers also mention social and practical concerns as contributing factors, too. Among these are: social stigma related to addiction, public and community understanding of addiction treatment, and importantly, doctors’ fear of harming the patient-physician relationship, cited in 56% of the selected publications. Also included were practical concerns for medical offices, such as health insurance reimbursement for care.

Together, these factors serve as negative deterrents to discussing addiction, let alone treating it. Why should a doctor expose herself to criticism from patients, peers, and bosses, if the patient doesn’t overtly ask for help? Denial of a patient’s addiction may not be conscious, nor stem from malice. It could be the most rational response of an overworked and time-constrained physician.

Patients may not take issue with the status quo of silence, either. “If my doctor didn’t say anything… I must be just fine compared to others,” a patient in denial might tell themselves.

Physicians’ View of Addiction

Perceptions of institutional support may play a role in the reluctance, but it isn’t the only deterrent. As NIH notes, 74% of doctor responses in this sample stated “insufficient skill” as a reason not to address addictive behavior.

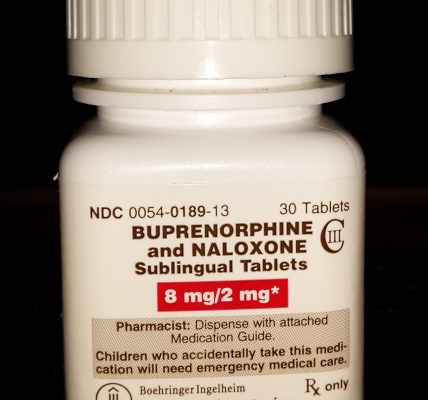

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), over 21 million Americans suffer from a substance use disorder, yet only 3,000 doctors are specially trained to treat them. By default, this means the public must rely on general practitioners or other health care specialists to identify and treat addiction.

Even in ideal circumstances and operating with the best intentions — increasingly difficult due to systemic stressors placed on healthcare providers — it may be unrealistic to think doctors have the capacity to stay current on the latest addiction research and treatment.

This is why A Unified Theory of Addiction, by Dr. Robert Pretlow, could be empowering for physicians and patients alike. If all addictions share a common cause, as Dr. Pretlow posits, helping patients overcome addictions shares a common path forward, too.

Dr. Pretlow, a childhood obesity expert, president of eHealth International, and publisher of AddictionNews, roots his theory in the stress response. In short, if stress can’t be resolved it is displaced. In humans, stress relief takes many forms, and when combined with addictive substances, can become decidedly unhealthy.

What if physicians could begin their treatment plans from a single, unified theory of addiction? Wouldn’t that provide greater confidence in their ability to help a patient? Wouldn’t it remove some of the stigma of addiction? Might it help alleviate the perception that addiction treatment is hopeless, a view shared by too many institutions and individuals alike?

Fewer Physicians, Less Capacity to Treat Addiction

“Do no harm” extends to “do nothing at all” due to a towering shortage of doctors in the U.S. workforce. Here, Americans at large are in denial.

Access to a doctor, even one without specialized training in addiction is, for an increasing number of Americans, a luxury. Data published by the AAMC in 2020 estimates an ongoing shortage of 54,100 to 139,000 physicians by 2033. This shortage spans primary- and specialty-care fields, including addiction specialities.

There is a range of contributing factors to this shortage of doctors. Contributing factors include: an aging population, immigration visa restrictions, the costs of education, the physical and emotional demands of practice, the economics of providing service, and more. All place pressures on American healthcare. People seeking substance use treatment with physician oversight and care are just one population group in need.

For people who wish to seek treatment through the care of a doctor, our society needs solutions, first, to ensure we have enough doctors, including increasing the numbers of physicians trained specifically in addiction treatment and recovery. Second, we must build and maintain work environments where medical doctors feel empowered to address substance abuse and addiction concerns with their patients. Institutions need to look at the messages they send doctors when it comes to addiction treatment.

The latter will be made easier if we can reduce the stigma associated with addiction care. Social change begins when we set a foundation of hope that treatment is possible. A unified theory of addiction goes further, providing common ground from which to embark on a healing journey.

Written by Katie McCaskey. First published October 14, 2024.

Sources:

“Doctors reluctant to treat addiction most commonly report ‘lack of institutional support’ as barrier,” National Institute of Health, July 14, 2024.

“Physician Reluctance to Intervene in Addiction: A Systematic Review,” JAMA Network, July 17, 2024.

“What Research Reveals About Doctors’ Reluctance to Address Addiction,” University of Colorado, School of Medicine, July 29, 2024.

“A Unified Theory of Addiction, Preprint 5,” Dr. Robert Pretlow, March 2023.

“21 million Americans suffer from addiction. Just 3,000 physicians are specially trained to treat them.” AAMC, December 18, 2018.

“The U.S. Physician Shortage Is Only Going to Get Worse. Here Are Potential Solutions.,” TIME, July 25, 2022.

Image Copyright: armmypicca.