Anorexia, Gambling, and the Anticipation Wrinkle

Two previous posts discussed the convoluted reward system on which all humans operate to a greater or lesser extent. Related to this is a trait shared by anorexics and pathological gamblers, and possibly by others, too, whose obsessions might need to be looked at from different angles, though all related to dopamine:

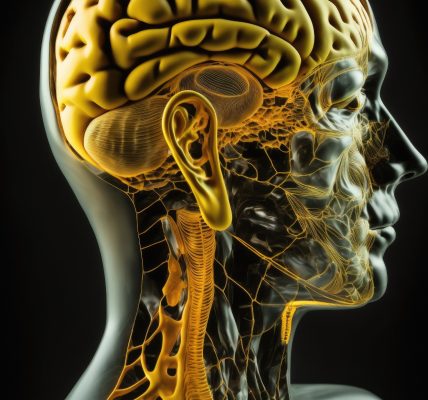

This chemical is produced in the part of the brain that is associated with reward. When someone experiences a reward — say while eating a really good meal — their Dopamine level spikes. For addicts, the opposite is true: That spike in Dopamine only comes in anticipation of the reward, as opposed to the actual reward itself. Later, once the reward is gotten, the effects are blunted because the brain has been flooded with dopamine as it thought about eating.

Incidentally, a 2017 paper describes the endocannabinoid system (ECS), which shares this dual nature and plays a part in energy balance, and explains the relationship between dopamine and “the munchies.” The endocannabinoid system is involved in every aspect of the search for, intake of, and bodily use of calories, and this includes people with both obesity and type 2 diabetes, as well as other less easily definable conditions. Cannabis was first used to treat loss of appetite, but…

Interestingly, ancient Indian texts also report the use of potent preparations with high dose of cannabis by ascetics to overcome their hunger.

In 1971, came the first study with a controlled amount of oral THC consumption in young healthy subjects. A significant increase in food intake was observed after cannabis use when the subjects were already fed…

Soon afterward, another study showed a contradictory anomaly: that while a low dose would increase appetite (bringing on “the munchies”) higher amounts (or what in the trade are called “heroic doses”) would suppress appetite. Back in 2012, in a piece that can no longer be found on the Internet, Dr. Vera Tarman wrote that when not eating, the anorexic patient “is experiencing a dopaminergic euphoria,” in other words getting high off caloric deprivation. The hungrier a person becomes, the more the food’s reward value increases.

The anorexic does not eat food, but as he or she gets hungrier, she or he instead anticipates food — in the food preparation, in the food obsessions, in how she or he ‘plays’ (but does not eat) the food… [T]his is a dopamine high which builds and builds the hungrier the person gets. And, importantly, it stops the moment food enters the body. Anorexics resist food the same way as the drug addict resists withdrawal from their drug.

It is worth looking back at a 2013 paper titled “What motivates gambling behavior? Insight into dopamine’s role.” The author first notes that dopamine is “the chief neuromediator of incentive motivation,” and while actually in a gambling situation, pathological gamblers (the compulsive and addictive kind) possess more dopamine than healthy individuals do. However, more than 10 years ago some curiosity-tweaking studies indicated that dopamine release…

[…] seems to reflect the unpredictability of reward delivery rather than reward per se. This suggests that the motivation to gamble is strongly (though not entirely) determined by the inability to predict reward occurrence.

“The inability to predict reward occurrence” turns out to be a very resonant phrase. A rather bizarre related study later showed that gamblers not only obtain a dopamine reward from the unavoidable anticipatory doubt — but that they obtain more of a dopamine reward from losing than they do from winning.

At any rate, to characterize two reactions as polar opposites, to view anticipation and reward as opposite and mutually exclusive entities, could be to seriously misread the situation. Apparently, the whole phenomenon is more subtle. An approximate comparison might be drawn with sneezing. Many people enjoy the anticipatory, almost unbearable seconds when the sneeze builds up. The resolution, the actual sneeze, is almost anticlimactic, and when matched up with the gambling analogy, either winning OR losing is the actual sneeze. The fun part is the buildup.

So, we need dopamine to inform us, on an intimate physical level, that we have indeed received something we wanted, and maybe even something that we never knew we wanted. Apparently, we also need dopamine to tell us to want things. The dopamine of anticipation can never let us down. It is its own reward. It can never betray, or disappoint. The actual reward, the anticipation, can never be damaged, rescinded, stolen, misplaced, forfeited, or seized. It is the metaphysical equivalent of the perpetual motion machine. It defies what we previously thought of as the rules.

For additional dopaminergic complications, a more recent piece by Susan Cunningham quoted behavioral health counselor Amy Goodwin on how substances provide the illusion that we are handling stress and other psychic discomforts, but without actually changing our behavior or improving in any real way. This is why substance use became known as a crutch, because while a person with a crutch may be able to walk, they are still incapable of walking without one. So, in a manner of speaking, that is still the functional equivalent of being unable to walk at all. Goodwin explained how alcohol…

[…] causes the brain to over-release pleasure chemicals such as dopamine… The more we over-spend our dopamine, the less we have for day-to-day functioning. We can feel like life has become ‘boring’ and we now need alcohol…

The simplest assumption about gambling, that winning is the reward, turns out to be not so cut-and-dried. Actually, pathological gamblers “report euphoric feelings comparable to those experienced by drug users.” And remarkably, the more money they lose, the more they persevere — not out of anxiety to recover the losses, but for the pleasure inherent in the “inability to predict reward occurrence.” Or as some might put it, the risk. Goodwin mentions another study showing “evidence that ‘near misses’ enhance the motivation to gamble and recruit the brain reward circuit more than ‘big wins.'”

The compensatory hypothesis could explain why losses are so important in motivating human gamblers: without the opportunity of receiving no reward, gains become predictable, and hence most games become dull.

Again, the excitement of risk is paramount.

Written by Pat Hartman. First published July 19, 2024.

Sources:

“What Happens to Your Brain on Sugar, Explained by Science,” Mic.com, April 24, 2024.

“Endocannabinoids and metabolism: past, present and future,” UCSD.edu, 2017.

“Finally Sober, Suddenly Fat: Food Addiction is Another Drug Addiction,” RecoveryWireMagazine.com, March 2013.

“What motivates gambling behavior? Insight into dopamine’s role,” NIH.gov, December 2, 2013.

“How substance use disorder often begins,” UCHealth.org, October 6, 2022.

Image Copyright: eclesh/ATTRIBUTION 2.0 GENERIC.