Chaos Behind the Wheel

Addiction is very much a self-perpetuating cycle, as journalist Yasemin Saplakoglu learned from researcher Erin Calipari. This is because cocaine and opioids take it upon themselves to appropriate the brain’s learning circuits and alter them to suit the drugs’ own needs. More rudely stated, these substances hijack the brain as efficiently as a young hoodlum out for a joyride on a Saturday night. One of Calipari’s quotes is,

Drugs essentially take the normal systems we have in our body and drive them in a way that makes you want to take drugs again.

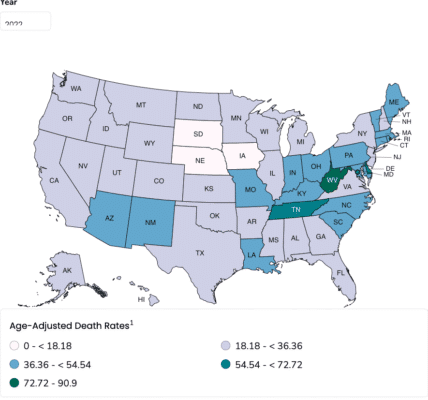

Fascination with the raw basic neurobiology of how that can happen has inspired her all along. Since 2017 she has presided over a laboratory where substance use disorder, and addiction itself, are urged to give up their secrets. This goes on at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, described as “an epicenter of the opioid epidemic.”

Just earlier this week, in fact, The Tennessean reported on “an epidemic of deadly overdoses” locally. The authorities even ask ordinary citizens to carry around Narcan, especially in the downtown area where the odds of encountering an unconscious overdose victim are greatly increased:

Fentanyl has been the leading contributor to fatal overdoses and was found in over 50% of cases for the first time in 2018. During the pandemic, fentanyl was found in 76% of cases, and that has remained unchanged since…

In the past four years, around 2,500 of Nashville’s deaths have been by overdose. Opioids no longer hold a supreme position, as other classes of drugs take down increasing numbers of people.

A caption in Saplakoglu’s article reads, “Addiction is challenging to study because it shows up differently in different people: Even which neural pathways rewire vary from person to person.” It affects their ability to learn anything at all. The researchers, however, are learning. A point that Calipari makes strongly is that some perceptions about addicts are mistaken:

When you think of addicted people, you’re thinking of these stereotypical images we have of people injecting drugs and passing out. But that’s not the biggest population of people suffering from substance use disorder. They’re nurses. They’re teachers. They’re doctors. They’re athletes.

Once again, the term “multifactorial” is appropriate. Just like regular people, addicts are different according to their history, circumstances, and cellular composition. Some thrive on uppers, while others require downers to even function — and vice versa.

Returning to researcher Erin Calipari, she is concerned with the overall effects on society at large. Every addict is surrounded by relatives and friends, or by social workers and law enforcement officers, but whatever the environment, one individual’s habit can impact and influence innumerable others, whether strangers or known to the person. “Addiction affects the lives of everybody.” It is easy to see what Calipari’s addiction is:

Learning about the next thing and solving hard problems is in and of itself super satisfying. Then when you take a breath and take a step back and realize that those hard problems you’re solving really impact people — it then makes it even kind of more meaningful.

In many cases, men and women react differently to the substances that control them. Calipari lists other potential discrepancies:

Some people suffering from addiction have comorbid disorders like anxiety and depression. Some people are taking drugs because they are trying to avoid pain. Some people have compulsive behavior, and some do not.

Drugs are convincing our brains, “Yes, this is important. This is something we need to do again.” Drugs drive not only decisions about the drug itself, but also decisions about non-drug stimuli in our environment. They change how we learn.

This transpires at the molecular level. More drug use equals less dopamine in the brain, so it becomes harder to learn new things.

Addiction basically makes people quite a lot more stupid than they were to begin with. In particular, they seem unable to draw cause-and-effect conclusions between their own actions as addicts, and the undesirable results that happen to addicted persons as a general rule:

Sometimes it’s sad to talk to people who are suffering from substance use disorder, and I don’t know how to help them. They’re asking me questions as an expert. But I’m an expert on the specific neurobiological changes that occur. It is hard for me to understand the impact of this disorder on the day-to-day life of an individual since I have not personally experienced it.

[W]omen are more likely to report taking drugs to avoid or escape negative consequences, like stress and anxiety. Men are more likely to take drugs impulsively, to get high and to hang out with friends. Both sexes are taking drugs, and some percentage of both will develop substance use disorder. But they’re doing it for different reasons.

How addiction manifests itself can vary. Some people are ashamed and self-loathing, while others not only admit that their substance of choice is the most important thing in the universe to them, but actively ensure that the substance, and their having it or not having it, becomes a very important factor to everyone around them.

The neurobiology of addiction is one of the strongest forces to affect human behavior. How a particular person reacts can depend on their financial situation, their sex, and even familial genetics. It’s physical too, and “Which neural pathways rewire because of addiction can also vary widely among individuals.” What they all have in common is the addict’s moral code, according to which the entire point and purpose of every other earthly action is to get the desired substance into your bloodstream as quickly as possible.

Written by Pat Hartman. First published May 31, 2024.

Sources:

“She Studies How Addiction Hijacks Learning in the Brain,” Quanta Magazine, December 7, 2012/23.

“Deadly overdoses persist in Nashville, Metro Health report says,” The Tennessean, May 24, 2024.

Image Copyright: LorE Denizen/CC BY 2.0 DEED.